Spartacus Movement

Influenced by the Mexican renaissance of the 1920s, Juan Manuel Sanchez (1930), Ricardo Carpani (1930-1996) and Mario Mollari (1930-2010) envisioned Argentinian arts liberated from colonial suppression. These three men were native to Buenos Aires and came from working class families. In 1956, they began creating and exhibiting artwork together, setting forth to reinvigorate Argentina’s cultural landscape and create an aesthetic that reflected the realities of the working class.

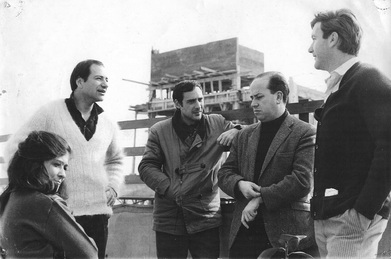

In 1959, Rafael Squirm, curator of the Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires, suggested that Sanchez, Carpani and Mollari, along with Esperilio Bute (1931-2003), and Carlos Sessano (1931), formally come together due to their similar styles and themes. The group of artists agreed to Squirm’s proposal, and assembled under the banner of the “Spartacus Movement”. Later that year, Bolivian painter Raul Lara joined the group, and in 1960 three new members were added: Elena Diz (the group’s only female member), Pasucal Di Bianco and Franco Venturi (the only member of the group to disappear in Argentina’s genocide of the 1970s). Through artistic portrayal, these artists strove to reveal what the government hid from the people, and to create a new language that could impact artistic circles, intellectuals, labor groups and the public alike.

Great Latin American art had its origins in the work of David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco, and the Spartacus Movement built upon this legacy. Similar to the Mexican muralists, the Spartacus Movement believed in art as a public statement. They were committed to creating murals that expressed social values because the laboring class had been marginalized from bourgeoisie culture and the arts. The Movement’s manifesto was created by the initial five members and published in the journal Policy in 1959: “For a Revolutionary Art in Latin America”. This manifesto was the group’s first official statement regarding the need to establish an authentic Argentinian art movement that transcended artistic expression and defined the Argentinian people, because Argentina’s artistic milieu of the time was occupied by old European formulas. The group instigated modernism in Argentina by creating a truly national style that authentically reflected the grueling struggle and exploitation of Argentina’s working class. The Spartacus Movement labeled this style the New Figuration.

By 1959, the Spartacus Movement had coalesced into a high-profile artistic movement, and dominated the fine arts scene in Argentina. The members of the group each completed paramount works and murals around the country, expressing through art the harsh realities facing the public. While accomplishing much, the group was forced to disband in 1968 due to internal conflict and a quickly unraveling political scene in Argentina – some of the members were forced to flee to Europe. While remaining close friends (for the most part), individual group members went on to fulfill their own artistic ambitions. Today, the Spartacus Movement’s murals serve to instill strength and pride in the people of Argentina and to inspire new generations of artists.

In 1959, Rafael Squirm, curator of the Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires, suggested that Sanchez, Carpani and Mollari, along with Esperilio Bute (1931-2003), and Carlos Sessano (1931), formally come together due to their similar styles and themes. The group of artists agreed to Squirm’s proposal, and assembled under the banner of the “Spartacus Movement”. Later that year, Bolivian painter Raul Lara joined the group, and in 1960 three new members were added: Elena Diz (the group’s only female member), Pasucal Di Bianco and Franco Venturi (the only member of the group to disappear in Argentina’s genocide of the 1970s). Through artistic portrayal, these artists strove to reveal what the government hid from the people, and to create a new language that could impact artistic circles, intellectuals, labor groups and the public alike.

Great Latin American art had its origins in the work of David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco, and the Spartacus Movement built upon this legacy. Similar to the Mexican muralists, the Spartacus Movement believed in art as a public statement. They were committed to creating murals that expressed social values because the laboring class had been marginalized from bourgeoisie culture and the arts. The Movement’s manifesto was created by the initial five members and published in the journal Policy in 1959: “For a Revolutionary Art in Latin America”. This manifesto was the group’s first official statement regarding the need to establish an authentic Argentinian art movement that transcended artistic expression and defined the Argentinian people, because Argentina’s artistic milieu of the time was occupied by old European formulas. The group instigated modernism in Argentina by creating a truly national style that authentically reflected the grueling struggle and exploitation of Argentina’s working class. The Spartacus Movement labeled this style the New Figuration.

By 1959, the Spartacus Movement had coalesced into a high-profile artistic movement, and dominated the fine arts scene in Argentina. The members of the group each completed paramount works and murals around the country, expressing through art the harsh realities facing the public. While accomplishing much, the group was forced to disband in 1968 due to internal conflict and a quickly unraveling political scene in Argentina – some of the members were forced to flee to Europe. While remaining close friends (for the most part), individual group members went on to fulfill their own artistic ambitions. Today, the Spartacus Movement’s murals serve to instill strength and pride in the people of Argentina and to inspire new generations of artists.